Tightropes Revisited: Enjoyment is finding the right balance.

"Ministers are facing union pressure to make the curriculum more enjoyable for disadvantaged pupils after figures showed that school suspensions and expulsions have reached a record high." (Wright, 2024). What does making school 'fun' and 'enjoyable' look like? Here lies the problem.

Screenshot of The Times (as cited) 31 December 2024.

Perspectives in the education sector are heavily influenced by the setting in which a teacher has been educated, trained, and worked in, compounded by the key stage(s) they have experience in. Ask any EYFS teacher, and they will provide evidence and anecdotal talk based on their practice in schools to support the use of play as a vehicle for learning at the other end of the Foundation-KS5 journey, I have a very different perspective for the students I teach, one that I don't find to be uncommon in our profession. This blog writes through this lens - I'm not an expert in EYFS or Primary teaching, nor would I propose that I am.

The first issue to tackle is what is being used to measure "enjoyable", which is mired with confounding issues. Student voice can be used to gain some qualitative data, but what's "enjoyable" and "effective" are two different things; this will vary between student and their self-efficacy built over time and success in a subject area. Likewise, anyone that has had a pastoral conversation will tell you that relationships do matter to attitudes toward a subject. Additionally, we can look to the teacher, and ask what students enjoy. Here, we are faced with social-class biases (Lazar, 2012) which are not deliberate, but can be linked to attitudes around what "aspirational" looks like. Also, survivorship bias can often seen in working-class-raised teachers (I've been as guilty of this as any) - I discuss this in my Walking the Tightrope researchED talk and blog.

The problem lies in the incorrect assumptions that disadvantaged children being excluded is an indicator of the system failing children from disadvantaged backgrounds as a whole; this is simply not true. It is worth reflecting on Ian Gilbert's words in 'The Working Class - Poverty, Education and Alternative Voices' (2018):

"Not all working class children are poor.

Not all poor children are from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Not all children from disadvantaged backgrounds are in poverty.

Not all children in poverty are in absolute poverty.

Not all children in absolute poverty are vulnerable children.

Not all vulnerable children are at-risk, looked-after, free school meal or pupil premium children.

But, despite the best efforts of many, the education system is failing most of them."

George W. Bush warned of the 'soft bigotry of low expectations' and I fear that lowering our expectations of what students are capable of in a trade-off to make learning enjoyable for a small number of excluded students. Enjoyment may be linked to the curriculum offer a school has; whether it is restricted, or provides a breadth of learning opportunities for a young person to be able to 'shine' in their own way; this is worth exploring, certainly as the Arts tend to take a hammering when budgets are forced to be cut (all schools should value the Arts, in my humble opinion), and many 'trades' vocational courses are not taught in schools due to a lack of suitable staff, facilities, and funding. However, enjoying lessons or a subject takes more than a change of curriculum content, or broadening the curriculum; rather a shift in perspectives and the support given to students to find a passion is required. In the words of Bella Doswell and Katherine Jennick, Careers is "so much more than talking about jobs". There is an abundance of research published that focuses on social mobility and social disadvantage, and the barriers these place for young people, their families, communities and school leaders. The Careers and Enterprise Company summarise these well in their Ready for the Future report, and I discuss similar barriers in my masters thesis.

Working to embed Careers education as part of the pastoral framework has been a passion of mine for several years now. Largely influenced by being a career-changer and working in industry before teaching. I believe most teachers find their subjects enjoyable (If you've been pinged to teach out of specialism in a subject area you don't like, then you are most likely to buck the trend here!). We have been able to find something in our own education that interests us enough to take this learning past GCSE, through A-level and to university. This is not linked to our own social-class as children, but may have been encouraged by parents who had positive educational experiences and successes themselves, or by parents that understood that education was a way for a better life for their children.

In my experience, many students that have been excluded or are at risk of exclusion share a lack of self-efficacy as learners, lower career aspirations, and need more support to see positive futures for themselves. Parental engagement plays a significant role in the as not all parents view careers discussions or advice as their responsibility. Wilson et al (2020) placed parents into six distinct categories, and discovered that parents across all descriptors were becoming more disengaged with both education and career options due to the Coronavirus epidemic. This is yet another challenge that requires schools to scaffold support and have meaningful conversations about futures with young people; futures where they have agency in their outcomes with the adults in their lives acting as way-markers on their journey to success. This is where 'Careers' forms part of the suite of pastoral interventions and support we offer students.

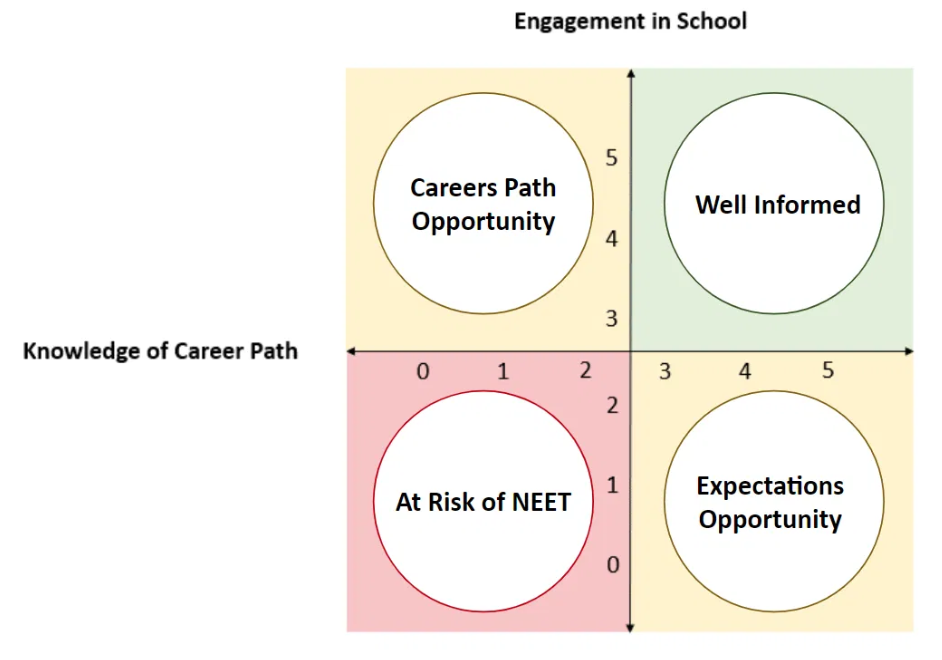

Meden Quadrants (Hill, 2022)

Meden Quadrants (Hill, 2022)

I devised the Meden Quadrants to address the types of careers interventions offered to students based on their need. Young people that present in the 'at risk of NEET' quadrant tend to have little idea of their desired career path, a poor idea of or challenges to meet the expectations which a school or an employer has from an academic/character stand-point. These students may have been given inaccurate careers advice from their own network outside of school, or may not have a network that has the experience to facilitate these conversations. Often these students will present a challenge to engage academically with subjects due to apathy and feeling out of control regarding their own career choices. This may also manifest in challenging behaviour in these lessons due to a drop in their attitude to learning, thus leading to removal from lessons, and potentially exclusion. To scaffold re-engagement and present opportunities to enjoy school-life we cannot rely on the panacea of education where students find a passion for a subject through the merit of studying it and a purely academic love of learning. We must be prepared to support tentative steps back to engagement through helping a student find a sense of purpose in education, and understand which barriers are present through mentoring.

Secondly, as teachers, we need to consider that feeling successful is inextricably linked to enjoyment when it comes to doing anything, and education is not exempt from this; in turn, this tackles self-efficacy and student motivation. If we adopt honest conversations about our qualifications and grading system with students, they can celebrate their own successes. A Grade 1-3 is a passing grade and a Level 1 qualification, lets make no bones about it. These will get a student onto a course at college, although they would need to resit English and Maths if they did not achieve a Grade 4, a Level 2 qualification. Once you change the language from "Failed/failing" to "Level 1/2 passes" students realise they are succeeding, and can embrace their next steps on a career journey. With successes comes a sense of achievement and enjoyment soon follows. When a young person that formerly could not envisage a positive next step following school realises they can achieve their aspirations, they become engaged in school. A sense of belonging, linked to success, forms. This needs to be scaffolded with opportunities to widen their network of employers, and mentoring to keep them on track, and not become NEET or excluded. It's a journey that's tailored to their needs, just like everyone's career development should be. This is how Careers can be woven into the pastoral framework in schools to benefit those most in need of engagement.

Lastly, employers are calling for employability skills to be taught in schools, and this is nothing new. I do not believe this is something which requires a complete rewriting of the school curriculum. Rather, embracing oracy programmes such as Voice 21's, and ensuring that messaging around employability skills is clear to all stakeholders; students and staff internally, families and employers externally. Using Skills Builder's framework alongside employability skills impact statements is a good place for faculties to start embedding careers into the curriculum. This isn't a skills-based curriculum re-write, more an acknowledgement that what we do teach students isn't explicit enough for those outside of education to be aware of, nor do students realise they are building their essential employability skills every day in school.

In conclusion, enjoyment comes through feeling successful, and knowing you have a positive future, with someone to guide you through this stage of your journey. Students focusing on their next steps will feel they belong in a school community, rather than believing their aspirations aren't 'enough' or valued by those most able to nurture self-belief in young people. We don't need a curriculum overhaul for the "disadvantaged", the current one has been raising standards well for thousands of disadvantaged young people for over a decade. What we need is a method of engaging the disengaged - finding a sense of purpose does that.