Walking the Tightrope

We walk a tightrope in education, balancing the ideal of students studying a subject they are passionate about and the pragmatics of a student studying because they need to for future employment. Teachers naturally want to encourage a love of their subject in the students they teach, but this can be at odds with students – more so when we come to Year 11 visiting colleges, returning with “I only need Maths and English” attitudes. There seems to be innate and extrinsic motivation working at odds here, when we can use the extrinsic motivation of getting a college place or earning money to develop the intrinsic motivation that develops a student’s belief in themselves and a positive future.

“Aspiration” appears in so many school mission statements, social media straplines, and their ethos. When viewed through the eyes of many this means high grades, an undergraduate degree, followed by the usual “aspirational” career choices which the press loves to remind us of when highlighting the achievements of those gaining a raft of Grade 9 GCSEs or straight A* A-levels with the “…is off to read law at <insert Russell Group university here>”. This is such a pervasive view that it trickles down through schools, parents and families, and finally students. The most heart-breaking comment I have heard on results day has been one kid tell another they “failed” a subject. They didn’t fail, it was a Grade 3.

I’ve long held the belief that schools need to be mindful of the language we use and be honest with students about where their grades sit, and what they will mean for their futures. This is now the direction I lead careers education within a school, and it has been instrumental to the whole school impact seen with our aspirations agenda.

When we consider that from a Careers perspective teachers can be guilty of middle-class biases when talking about aspirational careers and what success looks like. Teachers take their middle-class privilege for granted (Lazar, 2012). Indeed, from my own experience of graduating from university at 39 years of age, it has been clear to me that while I still try to hold on to my working-class roots it is incredibly difficult to claim to really remain working-class. I think the comedian Jason Manford deals with this conundrum with his term “muddle-class”. When speaking about this at conferences up and down the country, teachers nod and smile when realizing that as a profession we are guilty of aspiration meaning “more than a teacher” or that students from disadvantaged backgrounds should be choosing careers we would aspire to be if we weren’t teaching. In reality, aspiration as an agenda is best served when it is distilled to “be the best you can be, at whatever you choose to be in life”.

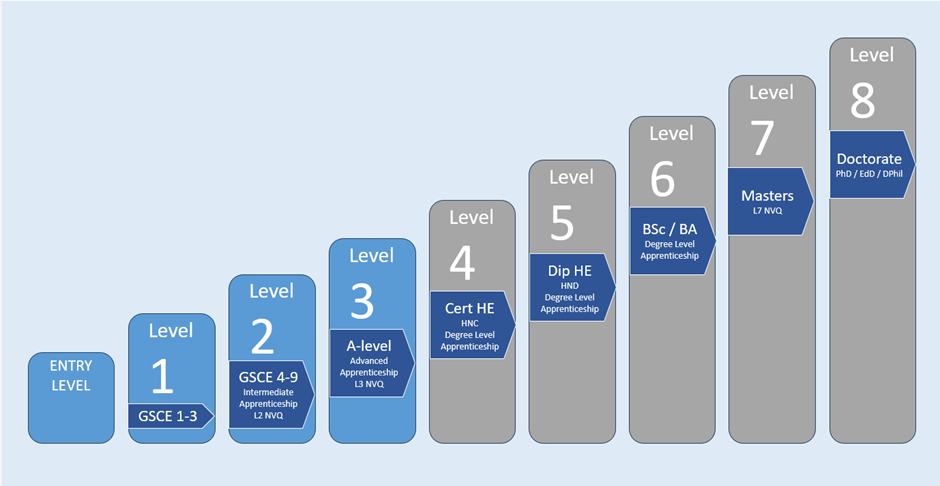

I’m not suggesting that schools should except underperformance. I’m calling for more schools to celebrate individual progress and support students to make informed decisions about their futures after they have been exposed to a curriculum that explores the world of possibilities that are open to them. With this shift, and a central tenet that stems from the belief that a school either has aspirations for all, or it fails in this aspect of community ethos, we can effect transformational change to the self-efficacy and tenacity that students develop during their time with us. So, as teachers, we need to lead a change in the language we use about the grades students are achieving in our subjects. The only grade considered a fail is a U, given qualifications follow a levelled structure, with secondary schools only really being concerned with qualifications between entry level and level 3 (see below).

Students come to us with differing starting points with SAT scores or CAT and ALIS scores providing a benchmark for likely grade achievement. Imagine being a student or parent of a student that is benchmarked for a Grade 2, making good progress throughout KS3 towards this, and excelling with Grade 3 in core subjects, only to be told that a Grade 4 is a “pass” - It is demoralising to say the least. Students switch off, resigned to “failing” and often thinking that their career goals are impossible. Sadly, this is often followed by a shift in attitude to learning, followed by behavioural issues that require additional pastoral support and intervention.

A simple change in the language we use, and honest conversations about careers feeds into a healthy culture of motivation and personal success. Students should never start their careers conversations with “I only want to be a…”, feeling they aren’t meeting adult expectations of success. Teachers should encourage students to excel in their career choices and refer any concerns through the appropriate channels. We should also congratulate student successes – “That’s a strong Level 1 pass, that’ll help you get on the right course at college”, and where possible, encourage self-improvement with “I reckon you’re not far from a Level 2 pass, and that would mean one year less at college!” or “If we push a little harder, we can turn this into a Level 2 pass, so you wouldn’t need to resit Maths/English at college, and can really focus on your chosen course”.

The role of the Careers Lead is now to show students that there are normally multiple paths to their career goals. A Foundation GCSE Science student that wants to become a Marine Biologist doesn’t need to take A-levels. There are more vocational routes available to them which will nurture the skills and provide knowledge key to their success at university. Likewise, a student gaining a Grade 5 can enter Nursing or Midwifery through a non-A-level route. The more we make this knowledge accessible to all, the greater the likelihood of positive student engagement.

Likewise, a student doesn’t “just want(s) to be a hairdresser/mechanic/bricklayer”, their will be many different factors feeding into this career aspiration (which will be another blog post). What is missed here, often due to not understanding the labour market and business structure, is that certainly in the case of hairdressing and construction, most qualified workers are self-employed or small limited companies that either hire a chair in a salon, or are subcontracted on a project. This means this student aspires to run their own business, and will probably aspire to expanding to having their own salon or running large projects that require subcontracting to other trades. They are an entrepreneur; a wealth generator in the local community; a job creator for the next generation. This is critical in areas of social disadvantage.

Now we have students building up their intrinsic motivation to succeed, because we are telling and showing them they can be successful, and highlighting the extrinsic benefits of continued success in a subject. The disengaged find motivation to become engaged, and those students who work incredibly hard to achieve grades below a 4, can see they are working successfully, and have a next step to their career aspiration to move up to.

There are three ideas that I hope students take away from their Careers education:

- Your education belongs to you. No one can ever take it away from you. It’s a key that will open doors for you in the future. Make the most of it.

- Education and learning is life-long. It will make you better at your chosen career or show you another path to take.

- You never have to settle. ‘Squiggly career paths’ are becoming more common, with people career-changing and having side-gigs to make money from the things they enjoy. Education gives you options to do this more easily.

At the end of the day, this is the magic we should be aspiring to in schools – each student has realistic career expectations, with a pathway and the self-belief needed for them to be successful throughout their lives.

Lazar, A (2012). The possibilities and challenges of developing teachers’ social justice beliefs. Online Yearbook of Urban Learning, Teaching, and Research.